What are the implications for the global South of China’s emergence as a digital superpower?

What are the implications for the global South of China’s emergence as a digital superpower?

A recently-published literature review from myself and colleagues at the University of Manchester identifies seven key issues that have so far emerged:

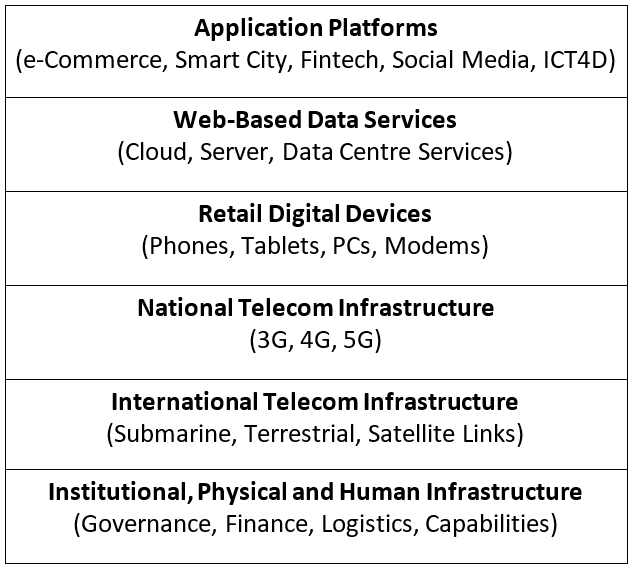

- Chronology: a steady progression of Chinese investment in the global South up the digital stack (see Figure 1) since the 1990s.

- Synergies and Tensions: an external image of “Team China” with strong state financial and political support for overseas growth of Chinese tech firms but, underneath, some strains between state and firms, and competition between the firms themselves.

- State Strategy that espouses mutual “win-win” between China and global South countries in public, but which has been single-minded in delivering benefits for China from its external digital strategy. Perhaps not so different from the approach of some Western nations.

- Design and Implementation: just a few nuggets suggesting Chinese digital developers may undertake “South-South” knowledge transfer e.g. from experiences in Chinese rural markets, but also that practice may differ quite a lot from the Principles for Digital Development.

- Impact: a delivery of economic and political benefits for China; a likely delivery of economic and political benefits for recipient countries in the South but with few well-researched examples; and a whole set of “concerns”. Talked up by Sinophobic researchers and talked down by Sinophilic researchers, the concerns include data security and sovereignty; control over digital infrastructure; dependency and vulnerability to Chinese state leverage; digitally-enabled inequalities both between and within countries; and environmental impact.

- “Digital Authoritarianism”: rhetoric in US-origin literature about China exporting digital authoritarianism seems to run well ahead of evidence, to ignore the many Western nations exporting surveillance systems to the global South, and to ignore that demand-pull from the global South dominates supply-push. But one should not swing too far the other way: China is now the South’s primary surveillance supplier, and the relationship between Chinese firms and Chinese state is not an exact mirror of Western equivalents.

- Global Digital Governance: a divergence of worldviews between the West and China on internet governance, digital standards, and data governance, with each side actively recruiting global South countries to their cause.

Figure 1: The Chinese technology stack

Although this research has been helpful, the rather small corpus of work so far published leaves not just a general knowledge gap around China’s digital expansion but also a specific six-part future research agenda:

- More Southern Voices: more Southern-based researchers, more South-focused empirics, and more evidence from Southern policy-makers, implementers, local tech firms, consumers, etc.

- Moving Up the Tech Stack: given the main research focus to date has been on telecom infrastructure there now needs to be more investigation of application platforms and services including e-commerce, smart cities, artificial intelligence, ICT4D projects, etc.

- Beyond “Team China”: moving beyond speculation to understand the actual coherence, collaboration, competition, and conflict between different Chinese state agencies, between Chinese state agencies and tech firms, between Chinese tech firms, and between Chinese ICT and non-ICT businesses.

- Between Sinophobia and Sinophilia: steering between the stereotypically-extreme views of some US and Chinese literature, and simultaneously steering between Sino-exceptionalism (treating China as a unique case) and Sino-identicaism (seeing China as just replicating patterns of Western (US particularly) digital imperialism).

- Local Agency: pushing past the neocolonialism of much current literature that focuses on Chinese and Western actors and sees those in global South as mere pawns in a new Great Game; to ask – for example – what room for manoeuvre global South actors have in procurement, in digital policy and in international forums; and to ask what digital alignment strategies they can best adopt.

- Local Development Impact: assessing the true cost-benefit of Chinese telecom infrastructure, data centres, platforms, etc., and the macro-level impact on local polities, debt, labour markets, etc.

Content in this post summarises the paper, “China’s digital expansion in the Global South: Systematic literature review and future research agenda”, published in the journal, The Information Society.

Get the full picture by reading the paper at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01972243.2024.2315875

Follow @CDDManchester