As a fashionable and novel tourism agenda, the theory of smart tourism is still evolving but the literature brings out three perspectives. First, tourists . The primary starting point of smart tourism is to fully satisfy the tourists’ need for scenic spots and create more value for them. In this sense, smart tourism is seen as a new pattern of tourism operation, which regards the tourist as the basic service object [1][2][3]. Second, managers (e.g., in government and tourism enterprises). Smart tourism is about achieving a comprehensive and thorough system which aims to offer accurate, convenient and ubiquitous tourism information applications, as well as a range of travel services [4]. In this case, the managers refer to the local scenic area managers and staff, government officials, and the company offering the technology [5]. Third, technology. Although the main point of the smart tourism system is the service, the capabilities and foundation of smart tourism is technology[6]. This refers to the highly systematic, detailed interaction between physical tourism and information resources [7], including digital data exchange[8].

Accompanied by the development of information and communication technologies (ICTs), the evolution of tourism goes through three stages: traditional tourism, e-tourism and smart tourism. Traditional tourism refers to people moving to countries outside their usual environment[9]. With evolution of technology, e-tourism emerged to address users’ interactivity and web-based technology was used to enhance the tourism experience and information governance, which is considered an early step of smart tourism[10].Subsequently, e-tourism evolved into smart tourism, building on technology infrastructure and ICTs (e,g. cloud service, big data). Importantly, smart tourism emphasises explicitly the support of variously smart activities and value-addition through the dynamic interaction between different actors[11]. The difference between e-tourism and smart tourism is detailed in the table below.

| e-Tourism | Smart Tourism | |

| Sphere | digital | bridging digital & physical |

| Core technology | websites | sensors & smartphones |

| Travel phase | pre-& post-travel | during trip |

| Lifeblood | information | big data |

| Paradigm | interactivity | technology-mediated co-creation |

| Structure | value chain / intermediaries | ecosystem |

| Exchange | B2B, B2C, C2C | public-private-consumer collaboration |

Smart tourism systems

Based on the development of ICTs, the smart tourism system (STS) is regarded as a complex system based on a digital service platform to support smart tourism, which addresses the innovation service provided to different stakeholders[7] [9]. Specifically, it emphasizes the actors’ intelligent demands of value-added through information service creation, delivery and exchange[13]. Thereby, the STS is characterized by value co-creation through the integration of sources into both micro and macro levels[3][8]. The table below presents the established system in China based on literature and reality [14][15].

| STS Sub-system | STS Functionalities | STS Instances |

| Forecasting system | Passenger flowWeather forecastQueuing-time forecast | Wind speed sensorHumiture sensorImage recognition |

| Panoramic virtual reality system | Virtual tourism experienceVirtual community | Panoramic photographyVR |

| Intelligent management system | Smart vehicle and transportReal-time traffic Crowd handling | RFID· Video surveillanceTourist-flow monitoring |

| Smart guide system | Scenic spot interpreterPersonalized tours route E/Robot tour map | Mobile app Electronic map Voice navigation |

| Smart recommend system | Scenic spot recommendation Recommended route | QR codeMobile app |

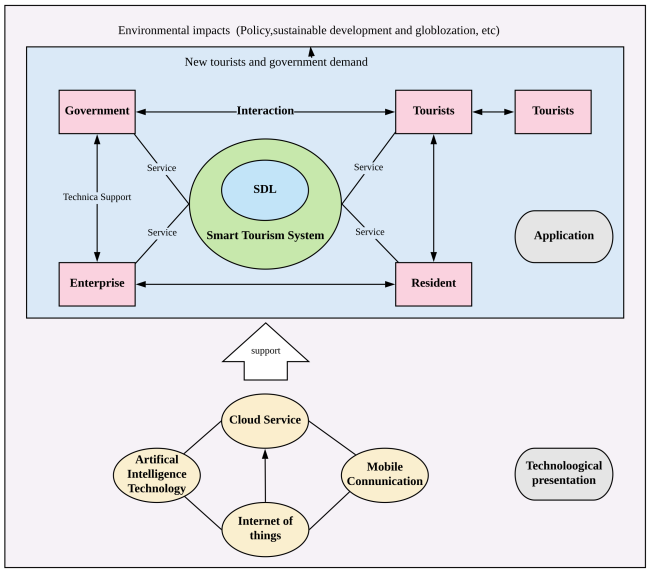

Figure 1 demonstrates the conceptual model of a non-profit smart tourism system, which is summarized from the current literature[15].The objective is that the STS provides service to government, enterprise, tourists, and residents [16]. Importantly, these applications are not isolated and individual but also service the interaction requirements. For example, from the perspective of tourism, the STS faces the tourist (T), the connection between tourists (T2T), and the interaction needs between the tourist and government (T2G).

Figure 1 A conceptual model of structuring STS adapted from [15]

Smart tourism ecosystem (STE)

When linking the ecosystem with the smart tourism system, an STE can be established, which contains the characteristic of both the smart tourism system and wider ecosystem components. An STE consists of two layers. The information ecology layer emphasizes the interaction between humans, firms, technology and their environment[9].This indicates the importance of the different actors related to information behaviour and information systems. The service system layer emphasizes the interactions through institutions and technologies to provide services to the beneficiaries, to exchange resources, and to co-create value [12].

Gretzel and Werthner defined the STE as “a tourism system that uses smart technology to create, manage, and provide smart tourism services/ experiences”[17].It is characterized by intensive information sharing and value co-creation. Buhalis and Amaranggana indicated that an STE aims to provide sustainable, enhanced/rich, valuable travel service and experience [6].To reach this, digital ecosystems that provide technical resources and facilitate interactions within and between stakeholders form the core of STE[17]. In other words, the generation of tourism experiences always requires extensive coordination and cooperation between different industry stakeholders and government players [18].

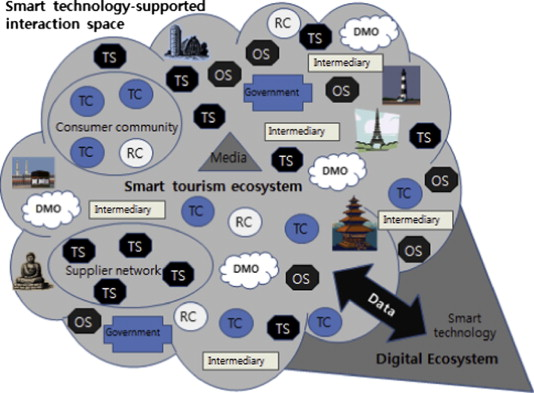

As shown in Figure 2, Gretzel & Werthner proposed a schematic representation of an STE [17].Their study describes an STE as an interactive space supported by a digital ecosystem and containing various types of actors, which are distinguished as tourism consumers (TC), residential consumers (RC), tourism suppliers (TS), other industry suppliers (OS), government agencies, destination marketing organizations (DMO) and intermediaries. These actors are not necessarily discrete, as a single player can play multiple roles. Moreover, this model is also adopted by other researchers like Brandt et al, who proposed an social media analytics (SMA)-enabled STE model, which also indicated the RC, TC, TS and government as vital actors [19]. The tourism consumers (TCs) have resources and, because they have access to the digital ecosystem, can be organized among themselves or mixed with closely related residential consumers (RCs) and act as producers. Through smart technology, tourism providers (TS) or other business-focused groups can connect and create new service offerings. In an ecosystem, the main source of ‘food’ for a ‘species’ is data/information, and the effective conversion of this food into rich tourism experiences can lead to a longer life for the ‘species’. Telecom companies and banking/payment support service providers representing other industry providers (OS) are vital ‘predators’ in the ecosystem and provide essential information to the system. Destination marketing organizations (DMOs) perform traditional information brokering, marketing, and quality control functions, while various intermediaries facilitate transactions through innovative data and devices [9]. Government utilization of social media in the STE could enhance the development and the value co-creation of local tourism [12].

Figure 2 Smart tourism ecosystem [17]

To conclude, STE studies regard the STE as a complex information and service ecosystem, which involves multiple actors like government, tourists, platform providers, residents etc. The main characteristics of STE are 1) the dynamic interactions between multiple actors; 2) the value co-creation during the actors’ interactions; 2) sustainable development; 4) the creation and exchange of tourism resources; 5) the innovation service. Thus, STEs could facilitate the interaction between actors, the exchange and creation of tourism resources, and value creation. This could further improve the tourism experiences and enhance the sustainable development of smart tourism.

References

[1] Yao, G. (2012). Analysis of smart tourism construction framework. Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications (The Social Sciences Edition), 14(2), 5e9.

[2] Fu, Y., & Zheng, X. (2013). China smart tourism development status and counter- measures. Development Research, 4, 62e65.

[8] Hunter, W. C., Chung, N., Gretzel, U., & Koo, C. (2015). Constructivist research in smart tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Information Systems, 25(1), 105–120.

[3] Shafiee, S., Ghatari, A. R., Hasanzadeh, A., & Jahanyan, S. (2019). Developing a model for sustainable smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, 287-300.

[4] Jin, W. (2012). Smart tourism and the construction of tourism public service system. Tourism Tribune, 27(2), 5e6.

[5] Huang, C., Goo, J., Nam, K., & Yoo, C. (2016). Smart tourism technologies in travel planning: The role of exploration and exploitation. Information & Management, 54(6), 757-770. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2016.11.010

[6] Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2013). Smart tourism destinations. In Z. Xiang, & L. Tussyadiah (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014 (pp. 553e564). Cham, New York: Springer.

[7] Law, R., Buhalis, D., & Cobanoglu, C. (2014). Progress on information and communication technologies in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(5), 727–750.

[9] Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2015). Smart tourism: foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 179-188.

[10] Werthner, H., & Ricci, F. (2004). E-commerce and tourism. Communications of the ACM, 47(12), 101-105.

[11] Lamsfus, C., Martín, D., Alzua-Sorzabal, A., & Torres-Manzanera, E. (2015). Smart tourism destinations: An extended conception of smart cities focusing on human mobility. In information and communication technologies in tourism 2015 (pp. 363-375). Springer, Cham.

[12]Park, J. H., Lee, C., Yoo, C., & Nam, Y. (2016). An analysis of the utilization of Facebook by local Korean governments for tourism development and the network of smart tourism ecosystem. International Journal of Information Management, 36(6), 1320-1327..

[13] Buhalis, D., Harwood, T., Bogicevic, V., Viglia, G., Beldona, S., & Hofacker, C. (2019). Technological disruptions in services: lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Service Management.

[14] Zhu, W., Zhang, L., & Li, N. (2014). Challenges, function changing of government and enterprises in Chinese smart tourism. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 10.

[15] Wang, X., Li, X. R., Zhen, F., & Zhang, J. (2016). How smart is your tourist attraction?: Measuring tourist preferences of smart tourism attractions via a FCEM-AHP and IPA approach. Tourism Management, 54, 309-320.

[16] Zhang, L., Li, N., & Liu, M. (2012). On the basic concept of smarter tourism and its theoretical system. Tourism Tribune, 27(5), 66–73.

[17]Gretzel, U., Werthner, H., Koo, C., & Lamsfus, C. (2015). Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism smart tourism ecosystems. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 558-563.

[18]Mill, R. C., & Morrison, A. M. (2002). The tourism system. Kendall Hunt

[19]Brandt, T., Bendler, J., & Neumann, D. (2017). Social media analytics and value creation in urban smart tourism ecosystems. Information & Management, 54(6), 703-713

Are we seeing a return to the old notion of a “third world”?

Are we seeing a return to the old notion of a “third world”?