Who wrote the first research paper about e-government?

I’m going to nominate W. Howard Gammon writing in Public Administration Review in 1954. Please comment with earlier nominations, but otherwise, W. Howard Gammon becomes the godfather of e-government research.

Of course Gammon’s review article: “The Automatic Handling of Office Paper Work” doesn’t mention e-government: according to Heeks & Bailur’s “Analyzing e-Government Research”, “The term ‘electronic government’ seems to have first come to prominence when used in the 1993 U.S. National Performance Review, whereas ‘e-government’ seems to have first come to prominence in 1997.”

However, Gammon is writing about the use of ICTs in the public sector: which is a common definition of e-government. Hence, his is an article about e-government, even though computing was just in its infancy with, as he notes, some technical literature available but very little written for a management audience and nothing – until his review article – for a public management audience.

In some ways things were very different then. Even by around 1990, there were more than 1 million computers in use across the US federal government. Back in 1954, there were roughly forty computers installed in total, half “large-scale” such as the UNIVAC I (weight 13 tonnes, c.2,000 operations per second, memory <1kb; cost c.US$10m in today’s terms) and half punch-card-based “baby computers” such as the IBM-604 (c.100 cards per minute, program of up to 40 steps, monthly rental cost c.US$5,000 in today’s terms plus a shift team of 2-10 supervisors and operators). Most were in the Department of Defense with a few in the Atomic Energy Commission, Census Bureau and Bureau of Standards. There was a pilot application to automate selection of optimum procurement bids, and plans to apply computers for use in air traffic control, taxation and weather forecasting. These applications were part of a broader expenditure (in 1952) of more than US$1.5billion (c.US$12billlion in today’s terms) on “adding, accounting and other business machines” within US public and private sectors combined; by 2008, total spending on ICTs in the US was roughly US$1.2trillion annually – a one hundred-fold increase in spending on ICTs.

However, the more striking thing that echoes across the decades is not how different but how similar the issues in the 1950s were to those we still face today. The following examples illustrate:

a) Skill Set: E-Gov Needs Systems Skills More Than Technical Skills: “…it is not necessary to know how to make, or even to repair, these machines in order to make use of them. For the public administrator … the emphasis needs to be placed on how and when to use these new devices” (p63). Just so, for those learning today about e-government, understanding technical aspects is of relatively limited importance; much more important is to understand the application of the technology. Put another way, e-government must be approached from an information systems not an information technology perspective: “it is a systems job which depends more on knowledge of what must be done, and why, than on knowledge of what makes electronic computers tick.” (p73).

b) Skill Set: E-Gov Needs Hybrids: a socio-technical approach is required that combines understanding of the ‘business’ of government with knowledge about the application of technology. Such a combination could be undertaken within a team: a “joint effort between the business managers and the engineers, so that engineers may learn enough about the businessman’s problem to translate the requirements of the job into machine procedure and so that management staff may learn enough about the capabilities and limitations of electronic machines to allow management staff to visualize how the new devices can be applied and how the … organization must be changed to take full advantage of the capabilities of the new equipment.” (p67) Such a combination might also be effected within a single person to create a socio-technical “hybrid” individual. But in that case, it will be far easier to hybridise a mainstream manager than an IT person: “As the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company found in its study, it is far easier to teach company management specialists what they need to know about the possibilities and limitations of electronic data processing than it is to teach electronic engineers about the internal operating problems of the life insurance business.” (p73). The exact same findings were reported in the 21st Century for e-government in Chapter 12 of Heeks’ book “Implementing and Managing eGovernment”.

c) Implementation: E-Gov Needs Re-Engineering Not Just Automation: More than thirty-five years before Hammer’s exhortations to stop “paving the cowpaths” and stop “automating the mess”, Gammon had already identified the limited gains to be made from automation, and the need to start improvements by re-engineering the business processes of govenrment: “One quick generalization may be made: the introduction of an electronic information processing system is not like buying a new adding machine which can be plugged in as part of an existing established clerical routine. It would be foolish and wasteful to make the large investment required to install electronic methods without first conducting a careful study which begins with considering the basic objective of the operation” (p73) … “The effective application of electronic methods in a given organization requires a rethinking of its organization and procedures. When electronic methods are applied, many of the intermediate reports and steps in the transmission of information become unnecessary and should be eliminated.” (p72)

d) Implementation: E-Gov Needs Top Management Support: “Rapid progress can be made during such an investigation only if the management representatives are high enough in the organization to make the broad decisions regarding the methods of operation” (p67). In the same way, more recently, top management support is still identified as a key necessity in successful e-government projects and its absence as a key cause of e-government project failure.

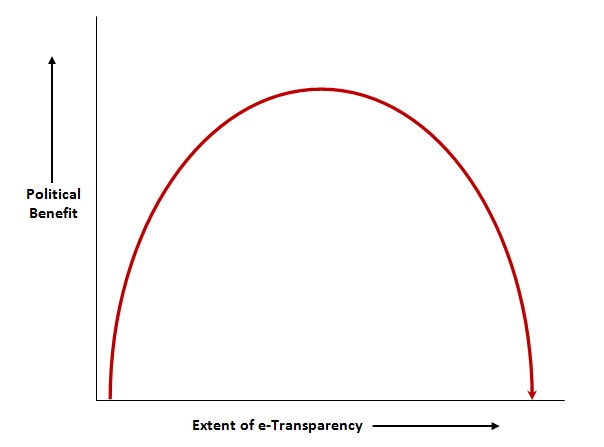

e) Implementation: Politics Matters in E-Gov: “there are organizational, procedural, economic, and social problems which must be resolved before automatic operation of … an office can be realized.” (p63). Some of these problems relate to internal politics given the danger that ICTs in government will cause “the disturbance of established bureaucratic empires” (p72), thus making political factors an important cause of e-government failure. This further explains why top management support is needed in implementation of e-government: “It also requires a broad point of view which looks to the good of the organization as a whole without being too much concerned about the effects of changes in methods on particular vested interests in the agency.” (p73).

f) Impact: E-Gov Affects Clerical Not Professional and Managerial Jobs: for lower-level clerical jobs, ICT brought the threat of “lowered prestige, relative decrease in real income, threat of unemployment, and routinization of many office skills” (p66). That has come to pass: around 25% of federal white-collar employees were in clerical/typing work in 1952. By the mid-2000s that had fallen to roughly 7%, largely as a result of new technology[1]. Meanwhile, skilled professionals would either be upskilled: “our accountants will then be free to do the more important job of analyzing and interpreting financial reports for management.” (p66) or unaffected: “there is no real possibility that the executive or the top administrator will become obsolete as the result of foreseeable advances in the use of electronic equipment.” (p73). And there were already signs that shortages of ICT professionals would slow the rate of e-government: “the shortage of qualified experts to design, build, program, and service these electronic data processing systems will keep this possible revolution from taking place rapidly.” (p67). More than fifty years later, Heeks (2006:101) still writes “The dearth of competencies is a major brake on the spread of e-government”.

g) Impact: E-Gov Impact Assessment Fails to Account for Total Cost of Ownership: there have always been ambitious claims for ICT in government e.g. that it “can make substantial savings and render better service” (p63). But on the savings side, e-government impact calculations often focus just on cost savings (e.g. of labour) but fail to include the costs of ICT. When the latter are taken into account, overall gains can disappear. Gammon’s paper is suggestive of this: he reports a case where preparation time for monthly reports fell from forty person-days to six/eight hours. Given clerical costs (in 1954 prices) of around US$200 per month, that would represent savings of about US$400 per month. Yet according to P.B. Hansen in “Classic Operating Systems” the IBM Card Programmed Calculator on which this saving was achieved cost US$1,800 per month in rental to which would have to be added the costs of calculator operations staff. Government’s tendency for lavish spending on ICTs was also already in evidence with reference to a Navy-organised symposium on “moderately-priced” computers; that criterion being defined as those costing (in today’s terms) less than US$1million.

Gammon’s paper is as much a review of then-current ideas about computing, drawn largely from the private sector, for a public sector audience as it is about computing in the public sector. However, this focus means it still stands eligible for recognition as the first e-government journal article.

How, overall, should we read it? I invite you to choose from its reflecting:

– “La plus ça change, la plus c’est la même chose”

– The failure of e-government practitioners to take note of key lessons known right from the start of IT in the public sector, given the continuing absence in e-government projects of many of the skill and implementation factors identified all those years ago.

– The failure of e-government researchers to find much new to say: you can see these same issues still in the conclusions of many of today’s e-gov journal articles.

Click here to link to a blog entry on the first application of e-government in a developing country.

[1] Though total US federal employment in 2009 – just under 2.1 million – was almost exactly what it was in 1952; albeit with a near-halving in DoD numbers.