Chen Sun, Louis Major, Nariman Moustafa, Rebecca Daltry

This blog focuses on a research study investigating the impact of Digital Personalised Learning (DPL) on pre-primary education in Kenya. The study features utilising A/B testing to examine the pedagogical implications and learning effectiveness of various design features in a classroom-integrated DPL tool.

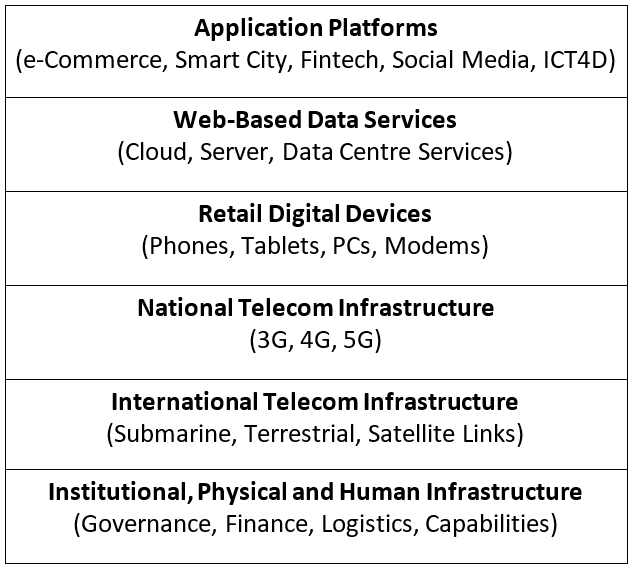

DPL is attracting increasing interest from researchers and practitioners, given its potential to adapt to individual needs and empower learners to determine their own pace and timing of learning [1, 2]. However, research on DPL to-date has primarily focused on high-income and well-resourced contexts, creating an opportunity to investigate its role in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [4]. Growing evidence indicates that DPL [6] could play an important role in improving learning outcomes in LMICs. For instance, DPL might help address challenges such as limited teaching resources, increase learner access to education inside and outside of school, enable remediation based on individual learning levels, and mitigate the negative effects of high teacher-learner ratios. Within the ICT4D community, there has been an expansive conversation on using technology to address development challenges and improve the quality of life in global south economies. Yet, there is scope for further discussion on the development of DPL in these regions.

Multi-strand Research on Integrating DPL in Kenyan Pre-primary Education

Researchers from the University of Manchester have been working as part of an EdTech Hub research study alongside other Hub colleagues, and in partnership with EIDU and Women Educational Researchers of Kenya, to investigate the development and evaluation of a DPL tool used by early-grade learners. In this context, an ambitious multi-strand research study (2022-25) is rigorously evaluating contextually appropriate pedagogical and software approaches for integrating DPL into schools in Kenya. The principal research question is: How can a classroom-based DPL tool most effectively support early-grade numeracy and literacy outcomes in Kenya? This research focuses on the use of the EIDU DPL tool, deployed on low-cost Android devices.

Research on Adaptivity and Data Feedback

This blog specifically explores one aspect of the larger multi-strand research study introduced above, focusing on adaptivity and data feedback. This particular study strand zeroes in on the question of designing and assessing various personalisation features in the EIDU DPL tool for pre-primary learning. In the study, one or two smartphone devices are distributed to each classroom. The learner-facing interface contains learning units targeting specific literacy and numeracy skills, and the teacher-facing interface (depending on the software version) can include lesson plans aligned with the Kenyan curriculum. The DPL tool also facilitates adaptive assessment and measurement strategies, generating continuous insights into learning. The main adaptivity feature of the DPL tool determines the sequence of learning content for a particular learner. To date, around 250,000 active learners from 4,000 pre-primary schools in Kenya are using EIDU.

DPL Adaptivity Feature Design Through Iterative Rounds of Software Interventions

Here, we reflect on the methods that facilitate this particular strand of research, which is concerned with the question: how can various adaptivity features of the EIDU DPL tool support classroom teaching and learning? One key area of our collaboration is to identify software changes that can be implemented within the DPL tool to test their effects on learning scores and engagement. Three iterative rounds of adaptive feature design have taken place, which have resulted in the development of four software interventions directed at learners, and five that cater to teachers. All nine software features aim at enhancing digital personalisation.

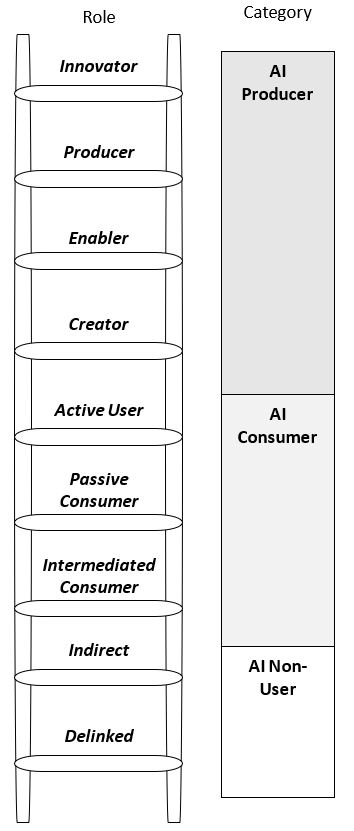

The learner-facing personalisation features focus on providing adaptive learning paths for individual learners. For example, one intervention tests different personalisation algorithms that are designed to select the most suitable learning activities based on the performance history of learners’ interaction with the DPL tool’s learning content. The designed algorithms select the next learning activity either to maximise scores or learners’ engagement level, as opposed to a learner progressing through a curriculum following a fixed sequence carefully arranged by educational experts.

The teacher-facing personalisation features explore how to meaningfully present learners’ data to teachers. The intended aim is to empower teachers with a better understanding of learners’ performance, enabling them to make informed pedagogical decisions and intervene when needed. For example, teachers can view a dashboard demonstrating learners’ progress and where learners are categorised in terms of competency levels per curriculum item. This EdTech Hub blog outlines further information on the nine interventions.

A/B Testing: A Software Design Evaluation Method

Understanding the impact of those personalisation features on learning and teaching poses a challenge. To address this, A/B testing is employed to test the comparative effectiveness of designed software features. A/B testing is a controlled experimental study for evaluating the efficacy of design elements by randomly assigning participants to different software versions [3]. This random assignment intends to minimise bias and ensures comparability between different software versions. Further, A/B testing enables continuous and unobtrusive large-scale experimentation, allowing for the assessment of design changes in technology-enhanced learning environments without interrupting regular teaching activities [5]. The purpose of implementing A/B testing in this study is to identify effective personalisation features that can enhance learning outcomes for pre-primary education in Kenya.

The personalisation design features are first pilot tested among a small sample of 20 pre-primary schools, where teacher feedback and classroom observations are obtained to further understand the user experience. When no abnormalities are detected during the pilot, the features are then released as an A/B test to EIDU’s mass user base of around 250,000 monthly active learners. The A/B test typically lasts for a school term, as this represents a predetermined period of time to ensure consistent learning experiences throughout the test duration.

At the time of writing, some of the tests are still running, with these scheduled to conclude by April 2024. Testing is continuously monitored by EIDU, and all data collected via the software is anonymised at source by assigning unique user IDs [3]. Since September 2023, the team have been analysing anonymous data to gauge the impact of those design elements. The findings provide direct input into the design and development of the EIDU tool in the Kenyan context and open up avenues for future research. For example, design features that lead to improved learning outcomes can be implemented as default settings, and new features can be launched as a series of A/B tests to continuously refine and optimise the DPL tool.

A/B Testing: Reflections on Opportunities and Limitations

The use of A/B testing in this research strand opens up new opportunities for understanding the impact of DPL tool design features on pre-primary learning in LMICs. By conducting a series of A/B tests, we are able not only to identify what works best from a pedagogical perspective but also to uncover how personalisation can be effectively integrated into classrooms at scale. Additionally, A/B testing allows for the optimisation of software design through continuous iterations and refinements without disrupting the user experience. This approach offers an innovative methodology in educational research, particularly for large-scale experiments involving a large number of learners.

Nonetheless, as A/B testing primarily focuses on software-generated data, it is important to acknowledge how some external factors which influence a learner’s performance may be overlooked. Thus, to gain a more comprehensive understanding, it is highly valuable to complement A/B testing with rigorous qualitative data, such as classroom observation. Additionally, there is a separation between researchers and the actual classroom environment. This detachment requires careful ethical consideration of matters related to data collection, usage and storage, in recognition of the distance between researcher and participant. To bridge this gap and ensure the transparency and accountability of the research, the team is committed to sharing a concise summary of findings and outcomes in an accessible format at the study’s end, available to all participants.

Despite these complex considerations, our experience with A/B testing suggests the potential of utilising this method in digital education research. Pioneering an innovative research method requires collaboration between multiple stakeholders, including but not limited to education researchers, data scientists, developers and educators, to think about the different pedagogical, ethical and technological elements involved. Sharing our insights with the ICT4D community is to invite a conversation on how A/B testing and other innovative research methodologies for large-scale software experiments can be adapted and refined for different research contexts.

References

[1] Bernacki, M. L., Greene, M. J., & Lobczowski, N. G. (2021). A systematic review of research on personalized learning: Personalized by whom, to what, how, and for what purpose (s)?. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1675-1715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09615-8

[2] Bhutoria, A. (2022). Personalized education and artificial intelligence in the United States, China, and India: A systematic review using a human-in-the-loop model. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100068

[3] Friedberg, A. (2023). Can A/B Testing at Scale Accelerate Learning Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Environments?. In: Wang, N., Rebolledo-Mendez, G., Dimitrova, V., Matsuda, N., Santos, O.C. (eds) Artificial Intelligence in Education. Posters and Late Breaking Results, Workshops and Tutorials, Industry and Innovation Tracks, Practitioners, Doctoral Consortium and Blue Sky. AIED 2023. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1831. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36336-8_119

[4] Major, L., Francis, G. A., & Tsapali, M.. (2021). The effectiveness of technology-supported personalised learning in low- and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52, 1935–1964. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13116

[5] Savi, A. O., Ruijs, N. M., Maris, G. K. J., & van der Maas, H. L. J. (2018). Delaying access to a problem-skipping option increases effortful practice: Application of an A/B test in large-scale online learning. Computers & Education, 119, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.12.008

[6] Van Schoors, R., Elen, J., Raes, A., & Depaepe, F. (2021). An overview of 25 years of research on digital personalised learning in primary and secondary education: A systematic review of conceptual and methodological trends. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52, 1798–1822. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13148

Recent outputs – on Digital China; Digital platforms; Digital agriculture; Digital health – from Centre for Digital Development researchers, University of Manchester:

Recent outputs – on Digital China; Digital platforms; Digital agriculture; Digital health – from Centre for Digital Development researchers, University of Manchester:

What is the status of AI rivalry between the United States and China?

What is the status of AI rivalry between the United States and China?

What issues should shape organisational digital-transformation-for-development (DX4D) strategy?

What issues should shape organisational digital-transformation-for-development (DX4D) strategy? What are the implications for the global South of China’s emergence as a digital superpower?

What are the implications for the global South of China’s emergence as a digital superpower?